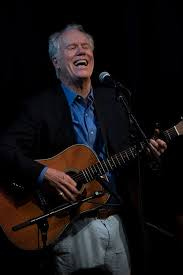

It was Kenneth Tynan, enfant terrible of postwar British theatre, who said he could not love anyone who did not love John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger. I feel similarly about Loudon Wainwright III. I have no recollection of when I first heard of him but it must have been at least forty years ago. One of many singer-songwriters to have been dubbed the “new Dylan” - at a time when Dylan was still very much in his pomp - Wainwright takes confessionalism to Plathian heights, writing lyrics that are not only painfully autobiographical but which often drag in members of his extended family.

As their fans know, the Wainwrights are to dysfunction what the Von Trapps were to Edelweiss. Among their number are Kate McGarrigle, Loudon’s former wife, who is no longer with us, his son Rufus and his daughter Martha. Rarely does anyone in a Wainwright song - including, it goes without saying, their lynchpin - emerge with their dignity intact. For a brief history of their tortured relationships I recommend ‘Meet the Wainwrights’ which was recorded on a cruise ship on the high seas when “the Wainwright familee” were the supper-time entertainment.

Loudon Wainwright III is 78 and despite creating a body of work that is sui generis and a treat that keeps on giving he is not as well-appreciated as he deserves. In that, of course, he is not alone, a fact that it’s pointless to bemoan. He is perhaps best known for his 1973 song ‘Dead Skunk (in the middle of the road)’ which, as Greil Marcus writes, had whole families singing along to it on their vacations: “The more you heard ‘Dead Skunk’, the funnier it got, but out of the blood and guts on the back road where someone five minutes or five hours before you had hit the thing you could feel an undertow, a self-loathing, a wish to disappear and never come back, to lose even your own name.”

While I laughed along with everyone else, I was never overly enamoured of ‘Dead Skunk’. More to my taste are the thirty songs gathered on the double-CD album High Wide & Handsome, which was released in 2009. I thought I had bought it but after scouring the house, I remembered I’d borrowed it from the music department of Edinburgh City Libraries. Thanks to Jeff Bezos, I now have my own copy and have been playing it ceaselessly since it arrived a week or so ago.

High Wide & Handsome is sub-titled ‘The Charlie Poole Project’. It’s Wainwright’s homage to his long-deceased fellow artist. A number of the songs were written by Wainwright and his collaborator Dick Connette, while others were either part of Charlie Poole’s repertoire or evoke his spirit and illuminate his life, which was not long; he was born in 1892 in cotton-picking North Carolina and died in 1931 after a monumental drinking binge. Fittingly, a banjo is carved on his headstone.

Even before he reached his teens Charlie played a home-made banjo. After a spell working as a millworker, his feet grew itchy - an incurable condition - and he took to the road, busking, doing odd jobs and getting into trouble with the law, usually as a byproduct of his drinking. To all intents and purposes, he was illiterate - he could “barely read a stop sign”, recalls his great-nephew, Kinney Rorrer, in the sleeve notes to High Wide & Handsome - but he managed nevertheless to lead a successful band. Signed in the mid-1920s for Columbia Records, he quickly recorded two sessions, sales of which, notes Rorrer, reached nearly half a million copies.

“When I heard that Loudon Wainwright was going to address himself to what Charlie Poole left behind,” writes Greil Marcus, “I didn’t know who was luckier. Poole might have been waiting all these years for someone to talk back to him so completely in his own language. Wainwright might have been waiting since he first heard Charlie Poole to get up the nerve to do it.” For his part, Wainwright says he first became aware of Poole in the early 1970s when visiting a friend called Patrick Sky. “Pat picked up a guitar (maybe it was a banjo) and sang me a bit of ‘Awful Hungry Hash House’ and the line ‘The beefsteak it was rare and the butter had red hair’ immediately made me do two things, almost simultaneously: 1) laugh out loud, and 2) wonder ‘Who the hell wrote that?’”

As Wainwright is at pains to point out, Poole did not write these lyrics. Nor did he write any of the songs he performed and recorded. What he did do, however, was make them his own and record defining versions of them. What is also clear is that Wainwright found a soulmate in Poole, and while High Wide & Handsome is a fitting tribute to him it is in no way an attempt to mimic him. Take, for example, ‘I’m the Man Who Road the Mule Around the World’, a traditional American folk song, with which Poole had fun, as is apparent in the following verse:

Oh she’s my daisy, she’s black-eyed and she’s crazy -

The prettiest girl I thought I ever saw

Now her breath smells sweet, but I’d rather smell her feet,

For she’s my freckle-faced consumptive Sara Jane

If I had to find one word to sum up Poole’s oeuvre I’d probably go for ‘Americana’, which I take to mean the authentic sound of American music. It’s a cocktail of folk, bluegrass, country, gospel, you name it, that has its acoustic roots in hardscrabble rural parts where music was - probably still is - an escape from the grind of making ends meet. These are tunes to make feet tap, pack dance floors, cause mourners to weep, and to bid the booze an unlikely adieu. Almost all the songs on the CD are sung by Loudon Wainwright, his delivery as pure as a mountain spring.

I have many favourites but the one that I love à la Tynan is ‘Where the Whippoorwill is Whispering Goodnight’, a gorgeous lament for a lost mother. On YouTube you can compare and contrast versions by Messrs Poole and Wainwright.

WRITING WORTH READING

A gentle reminder that tickets are now on sale for the festival of Writing Worth Reading (Royal Scots Club, 29-31 Abercromby Place, Edinburgh), which runs from 11-23 August. There are twelve events featuring a stellar cast: Steven Veerapen (James I and VI), Helen Percy (from pulpit to sheep pen), Magnus Linklater (Eric Linklater), Devi Sridhar (how to live to 100), Andrew Heaton (in the time of Trump), James Robertson (his cultural life), Bill Coles (Lord ‘Lucky’ Lucan), Mark Douglas-Home (the sea detective), Joseph Farrell (the art of duelling), Bendor Grosvenor (great British art), Rosemary Goring (Mary, Queen of Scots) and Liz Lochhead (her cultural life). Hotfoot it to www.royalscotsclub.com/events for details. To paraphrase Mr T. K. Maxx, when they’re gone, they’re gone.

Saw him in mid 70s in Glasgow. A few times since. Also capable of some sublime serious stuff. 'Dreaming' that Norma Waterson sings on The Very Thought of You is beautiful.

I am sure he also had a recurring guest spot on on of the early series of MASH, singing plaintive blues songs

LWIII was my first gig, in 1971, and one of the few things I'm proud of from my teenage years. Good to hear from another fan.